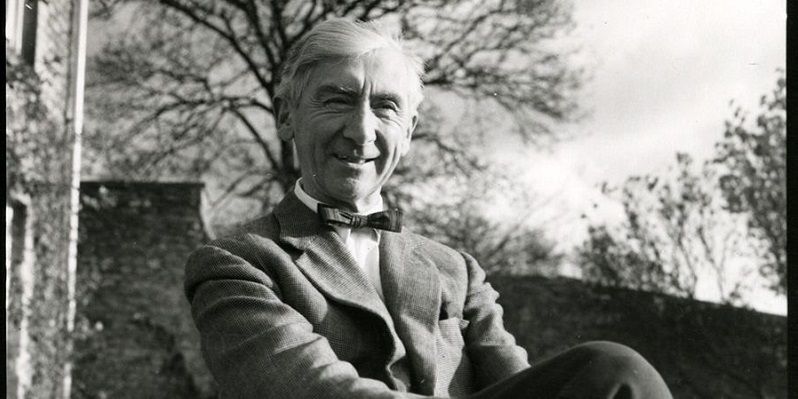

The Henry Moore Foundation's new research season features former Leeds student Sir Herbert Read.

For 30 years, a former Leeds student lived at the heart of of radical changes in 20th century arts and political thinking.

Now, Sir Herbert Read is being celebrated with a research season led by the Henry Moore Foundation in collaboration with the University. The 2022-23 season revisits Read’s achievements and will increase the public’s direct and virtual access to his comprehensive archive. It launches with a one-day workshop at the University for PhD and early career researchers.

In a recent Leeds alumni magazine, Rosalind McKever (History of Art 2005) wrote about Read’s abiding influence and his extraordinary life.

“READ ART NOW”. When I was a student at Leeds, this instruction – three gold words embossed down a red book spine – glowered at me from the shelf. I had not foreseen that a History of Art degree would require quite so much reading. Back then, Art Now by Herbert Read was just another book on the reading list. I was yet to understand that if it weren’t for Read, I probably wouldn’t have been studying modern art at all.

Sir Herbert Read (1893-1968) was a prolific writer of literary and artistic criticism, prose and poetry with 80 books to his name. Known to both friend and foe as ‘the Pope of Modern Art’, Read’s writing popularised new artistic movements within Britain and across Europe.

Read was driven by a belief that art was an essential part of life, intrinsic to design and crucial to education. Teaching children creativity was for Read an idea “packed with enough dynamite to shatter the existing educational system, and to bring about a revolution in the whole structure of our society.”

Born on a Yorkshire farm near Kirkby Moorside, Read showed literary talent from a young age. As a Leeds student between 1912 and 1915, he was an academic omnivore, studying law, political economy, social economics, European history and geology, alongside English and French literature.

Read’s artistic education came off-campus at the Leeds Arts Club. This society held weekly discussions on continental philosophy, theosophical spiritualism, radical politics and, crucially, modern art.

At the time, the Arts Club was run by Frank Rutter and Michael Sadler. Rutter, Curator of Leeds City Art Gallery, exhibited paintings by Paul Cézanne and Vincent Van Gogh. Sadler, the University’s Vice-Chancellor, had a private collection in his Headingley home, which included Paul Gauguin and Wassily Kandinsky alongside modern British art by the Bloomsbury Group. Read had backdoor access to the Vice-Chancellor’s collection through his mother’s friend Miss Wallace, Sadler’s housekeeper.

He became the real spearhead for England of the fight for modern art, contemporary art.

Read’s Leeds connections endured after cutting his studies short to fight in the first world war. He published his first book of poetry, Songs of Chaos, on his way to the front in 1915.

From the battlefields of Ypres, he sent a poem about his trench experience to The Gryphon, the Leeds student magazine, and he continued to write on politics and literary criticism. Injuries and honours, the Military Cross in 1917 and the DSO in 1918, brought Read to London.

There, he met TS Eliot who contributed to the journal Art and Letters, which Read had started with Frank Rutter. Eliot later invited Read to write for the literary powerhouse magazine The Criterion. As poet Hugh Sykes Davies recalled, Eliot, Read and Bonamy Dobrée (later Leeds Professor of English Literature) were “The three musketeers [...] of The Criterion”.

With a growing reputation as a literary scholar, Read published English Prose Style and Phases of English Poetry in 1928 and gave a series of lectures on William Wordsworth at Cambridge the following year.

Literary achievements were not enough to support Read’s wife, Leeds alum Evelyn May Roff (1894-1972), and their son John, born in 1923. Read joined the Civil Service, and the organisation wisely transferred him to a curatorial position at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

At the V&A, he was charged with care of the historic collections of ceramics and glass, seemingly a world away from the modernist painting he had discovered at the Leeds Art Club. However, Read’s sensitivity to abstract forms transferred well to ceramics and glass and he wrote a number of publications on the collection.

He continued to write treatises on literature and the decorative arts. He penned poetry. He ranged from Old Masters to modern painters like Edvard Munch and Pablo Picasso in his weekly slot in the BBC magazine The Listener.

This oscillation between the establishment and the avant-garde, the academic and the populariser, would define the rest of Read’s art historical career.

Broad knowledge earned Read prestigious posts. After two years as professor of Fine Art at the University of Edinburgh in the early 1930s, he resigned to avoid a scandal around his new relationship with musician Margaret Ludwig (known as Ludo).

He took editorship of the prestigious Burlington Magazine, then resigned when art collector Peggy Guggenheim asked him to become the founding director of a museum of modern art in London.

The enterprise was interrupted by the second world war, but his advice to buy both key movements in modern art, Surrealism and Constructivism, is today evident in Guggenheim’s museum in Venice.

Read defended modern art and artists at a time when they were unappreciated in Britain. “Herbert became the champion,” said his friend and fellow Yorkshireman, sculptor Henry Moore. “He became the real spearhead for England of the fight for modern art, contemporary art.”

Moore was Read’s neighbour in the north London artist enclave of Hampstead. Fellow residents of this “nest of gentle artists,” as Read termed it, were another Yorkshire-born sculptor Barbara Hepworth, her husband the artist Ben Nicholson, and the painter Paul Nash.

Teaching children creativity was an idea packed with enough dynamite to ... bring about a revolution in the whole structure of our society.

Read edited a kind of manifesto for English modern art, inspired by continental European counterparts, for the Nash-led group Unit One.

In 1936 Read helped Roland Penrose to introduce works by Salvador Dalí, Marcel Duchamp and René Magritte through the International Surrealist Exhibition. Read shared their interest in psychoanalysis with his utopian novel The Green Child, highly praised by his friend with some familiarity of the subject, Carl Jung.

To Read’s leafy suburb came a stream of Constructivist artists fleeing persecution for their art: László Moholy-Nagy, Naum Gabo and Piet Mondrian, plus Walter Gropius, the director of the Bauhaus. It was among these leaders in European modernist design that Read began to advocate for Constructivism in Britain. His book on this topic, Art and Industry, was influential on British designers of the 1940s and 50s.

Read’s political anarchism shifted his relationship with the art establishment during and after the second world war. His 1943 essay To Hell with Culture argued against the commodification of culture and separation of art and life.

With artists including Roland Penrose and Eduardo Paolozzi he created the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), rather than a museum displaying modern art in London. His projects focussed on living artists, including the Gregory fellowships at Leeds, which embedded artists and poets in the academic community.

Read’s support for younger artists demonstrated his commitment to personally expressive and politically engaged art. In the context of the Cold War, he coined the phrase ‘the geometry of fear’ when writing about the male British sculptors under forty exhibited at the 1952 Venice Biennale. Among them was Leeds native, Kenneth Armitage, whose sculpture Both Arms now welcomes visitors to Millennium Square in the city centre.

Read remained at the avant-garde for decades. However, when American Pop artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein began to turn art’s expressive qualities on their head, his enthusiasm for the latest trends waned.

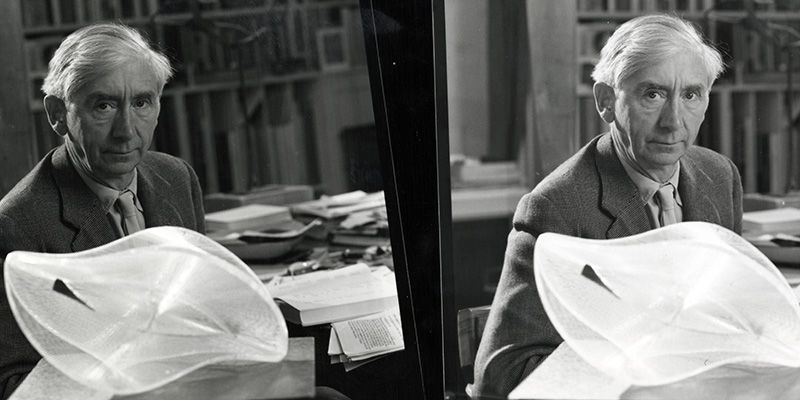

For all his anarchism, Read accepted a knighthood for services to literature in 1953. Yet he remained a staunch defender of artistic liberty until his death in 1968. “Herbert was terribly important” said Henry Moore. “He was the champion of the whole of the contemporary art in England.”

Read’s legacy is still felt across the worlds of art, design and literature.

His influence on Leeds alumni continues today, like with John Elderfield (Fine Art 1966, MPhil 1970, Hon DLitt 2006). “A pair of Herbert Read’s books spanned my undergraduate years in the department of Fine Art at Leeds: Art Now, published in 1963, and The Meaning of Art, published in 1966,” says Elderfield, who became Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), New York. “They were enormously influential upon my understanding of their subjects.

“If at times I found myself disagreeing with him,” Elderfield continues “I just had to remind myself: he went to Leeds as an undergraduate from a farming community in the North Riding of Yorkshire, as I had; so how wrong could he be?”

Connected – Herbert Read’s circle of friends

T.S Eliot

Read’s path regularly crossed with fellow poet and editor T. S. Eliot. As a poet, Read joined a who’s who of literary giants contributing to Eliot’s literary magazine The Criterion. Eliot and Read became lifelong friends.

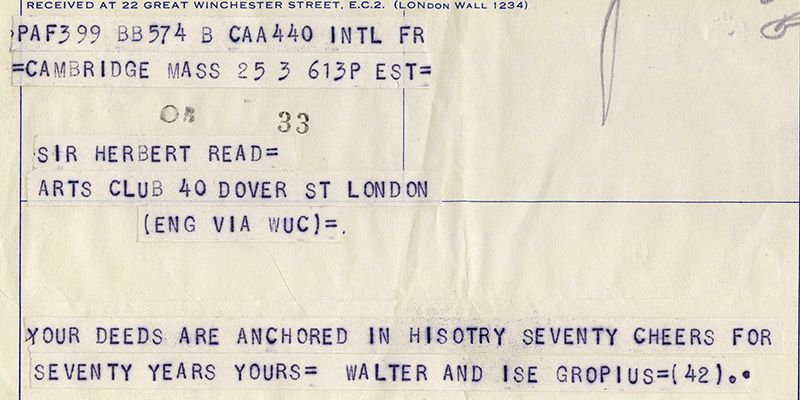

Walter Gropius

When he moved to Hampstead, the Bauhaus architect Walter Gropius joined what Read called “a nest of gentle artists,” which included eminent artists, writers and thinkers. Gropius and Read shared a belief in the essential need for art in life, be it in education or architecture.

Bonamy Dobrée OBE

Read and his friend, influential Leeds English professor Dobrée, compiled The London Book of English Verse. Along with Read, T.S. Eliot and Henry Moore, Dobrée was a driving force behind the Gregory Fellowships which brought eminent poets and artists to Leeds.

Peggy Guggenheim

Read advised art lover Guggenheim on which modern artists to collect. The fruits of their friendship can be seen in the remarkable Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice.

Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth

Read championed neighbours and fellow Yorkshire-born sculptors Moore and Hepworth who revolutionised 20th century sculpture.

Bertrand Russell

The anarchist Read collaborated and corresponded with philosopher Bertrand Russell. Read was one of the signatories for Russell’s Committee of 100, a trailblazing group that promoted civil disobedience. Both were also active in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Russell was a towering figure in 20th century philosophy who shared Read’s belief in anarchy and nuclear disarmament.

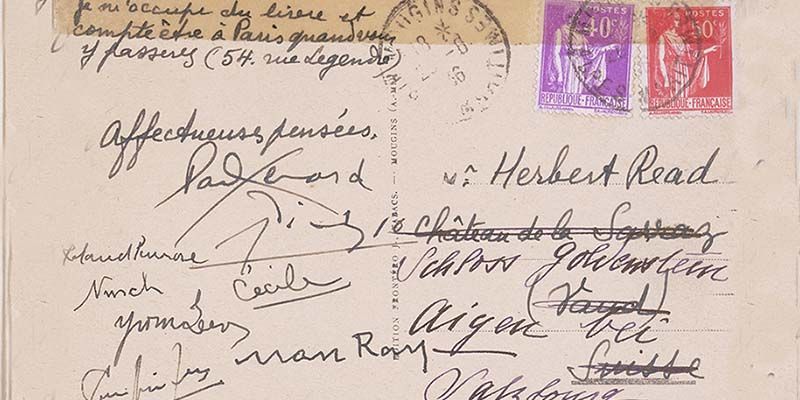

Paul Éluard

Surrealist poet Éluard sent Read this postcard to say he hoped to meet up in Paris. Others signing the card include Pablo Picasso, Cécile (Éluard’s daughter), Man Ray, Roland Penrose, Nusch (Éluard’s wife), Yvonne Zervos and Christian Zervos.

Dr Rosalind McKever (History of Art 2005) is a curator and art historian based in London.

Images: Special Collections, University of Leeds Library