Genetic testing should be used to help doctors spot high-risk cases of myeloma and enable targeted treatments, say researchers from the University of Leeds and The Institute of Cancer Research.

Up to one in four myeloma patients have genetic changes in their cancer cells that make the cancer more aggressive and harder to treat. Without targeted treatments, these patients face particularly poor outcomes and are at high risk of relapsing. Other patients without these genetic changes tend to stay in remission for five years or longer.

New research led by The Institute of Cancer Research, London (ICR), and the University of Leeds has shown that patients who carry two or more genetic changes – known as ‘double hit’ myeloma – are at more than twice the risk of their disease progressing early and almost three times more likely to die earlier with current standard treatment, compared to patients with a standard form of the illness.

The findings, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, have highlighted the unmet need in this group of patients, and led to calls for better access to early genetic testing and personalised treatments.

David Cairns, Professor of Clinical Trials Research and Deputy Director of the Leeds Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Leeds, said: “This study shows the most convincing evidence yet that multiple genetic abnormalities lead to poor prognosis for all patient groups.

“It was a pleasure to work with academic and industry collaborators from around the world on this federated analysis. The support of Cancer Research UK and Myeloma UK to the Clinical Trials Research Unit at the University of Leeds helped make this project possible.”

Genetic changes

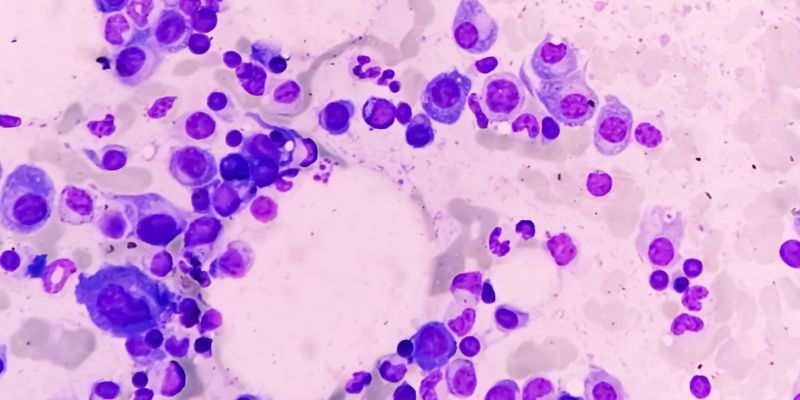

Myeloma is a blood cancer which starts in the plasma cells and each year approximately 5,900 people are diagnosed in the UK, according to blood cancer charity Myeloma UK.

Standard treatments include targeted drugs, chemotherapy and stem cell transplants.

There are typically around five or six key genetic changes, known as High-Risk Cytogenetic Abnormalities (HRCAs) that are used to classify myeloma as high risk.

In the new study, which was actively supported by many international myeloma study groups from Germany, Holland, Italy and Spain and industry partners, the researchers carried out a systematic review of 24 randomised controlled trials of myeloma treatment around the world in which data about HRCAs was included, over a 20-year period.

The results, involving in total 13,926 patients, showed for the first time that patients with two or more HRCAs were 2.28 times (more than twice) as likely to experience early disease progression than the control group (who had no HRCAs), regardless of the specific type of standard care treatment. Those with one HRCA were around 1.51 times more likely to experience early disease progression as the control group.

They also found that patients with two or more HCRAs were 2.94 times more likely to die from the disease early, compared with the control group, while patients with one HRCA were 1.69 times more likely to die early.

Because the project involved many studies over a long time, the researchers could tell that in newer trials, (those performed since 2015), the effect remained consistent. This reinforces that some high-risk patients need better, tailored approaches than current standard therapies.

Study leader Professor Martin Kaiser, Professor in Molecular Haematology at ICR and Consultant Haematologist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, said: “Myeloma is a very complex cancer. While current treatments can work very well for many people, there are others who do not respond well and may relapse early.

“Our research highlights the critical unmet need in this group of patients who are not benefiting from current standard treatment for myeloma. We’re aiming to find better ways of treating these patients and improving their outcomes.

“The results of this study have enabled us to more accurately classify the aggressiveness of an individual patient’s cancer. We would like all myeloma patients to be able to access the newer diagnostic tests which enable clinicians to group individual patients based on their risk profile and provide treatment that is tailored to their needs. We have already shown through the OPTIMUM trial that a more personalised approach involving five different existing drugs could help treat patients with the highest-risk forms of myeloma – helping keep them alive and healthy for longer.”

Tailored treatments needed

Evidence that tailored approaches can help patients with ‘double hit’ myeloma live longer was shown in the OPTIMUM MUK 9 trial, co-led by ICR, the University of Leeds and the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust. OPTIMUM MUK 9 was the first trial in the world to use state-of-the-art diagnostics to screen for high-risk myeloma, and to offer personalised treatment for those patients identified to have the greatest need at the same time.

The results of the trial showed that an intensive treatment regime of five drugs along with a stem cell transplant, kept the cancer at bay three times longer and doubled survival time for high-risk patients.

The results of the analysis have already informed good practice guidelines for more accurate diagnosis of myeloma patients by the British Society of Haematology and are set to contribute to international reference for genetic testing in myeloma.

However, the NHS has yet to adopt the results of the OPTIMUM MUK 9 trial. The trial was driven by UK academic researchers, who in partnership with the charity Myeloma UK, recognised the unmet need left unaddressed by standard approaches in daily practice.

The study received funding from Myeloma UK and Cancer Research UK and was supported by funding from the National Institute for Health and Care Research and the British Research Council.

Professor Kristian Helin, Chief Executive of ICR, said: “This study represents an important step forward in better understanding and defining the needs of high-risk multiple myeloma patients. Every cancer patient should have the opportunity for their cancer to be molecularly profiled to assess biomarkers that can give vital clues about how their disease should best be treated. Biomarker tests can tailor treatment precisely to the patients who will most benefit, which can both improve the lives of patients, and increase the cost-effectiveness of treatment for the NHS.”

Shelagh McKinlay, Director of Research and Advocacy at blood cancer charity Myeloma UK, said: “This work also shows the clear need for greater access to early genetic testing so we can target people’s cancer far more effectively. Until we have a cure, it is absolutely vital that myeloma patients are given the best chance to keep their cancer in check, and it starts with making sure they get access to personalised medicine.”

Further information

Top image: Myeloma cells in a bone marrow slide. Credit: Adobe Stock.

Co-Occurrence of Cytogenetic Abnormalities and High-Risk Disease in Newly Diagnosed and Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology on Tuesday 18 February.

Email University of Leeds Press Officer Mia Saunders at m.saunders@leeds.ac.uk with media enquiries.