Lockdown brought out the creative in us all. Millions of people discovered new hobbies, nurturing talents they never knew they had.

Professor Geoff Boxshall FRS (BSc Zoology 1971, PhD 1974) has been spending the time in his back bedroom identifying new species of tiny crustaceans called copepods.

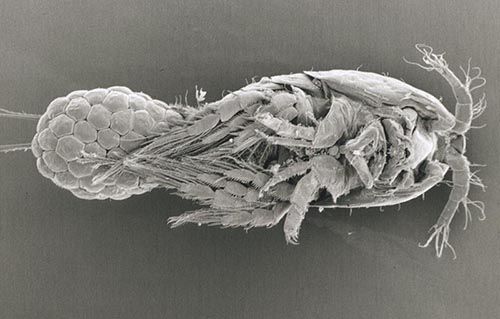

With the help of a colleague in Korea, he has described more than 300 new species in a small cluster of families of copepods that spend their lives as parasites of sea creatures called tunicates, or sea squirts. “I simply wouldn’t have done that at any other time,” says Geoff, long since retired as a scientist at the Natural History Museum in London.

One is entitled to ask – why? The answer is that Geoff has been fascinated by copepods (pronounced coe-pee-pod) his entire professional life, a love affair that began in his time at Leeds back in the late 1960s.

Copepods are arguably the most important creatures you probably haven’t heard of.

Although very tiny – most are about the size of a grain of rice – they are found wherever there is water, from the deepest oceans to lakes in the highest mountains, from pools formed by cup-shaped bromeliad plants in tropical forests to suburban puddles, and even in tap water.

“Copepods run the oceans,” says Geoff: “they are the link in the food chain between the phytoplankton and everything else”. Almost every fish in the ocean feeds on copepods at some stage of its life. A fish’s oily flesh is due to copepods in its diet. Copepod faecal pellets sequester a vast amount of carbon. They sink down from the sunlit surface waters of the ocean and are an important part of the carbon cycle.

Live copepods also have a potential use against malaria, as they can be released into water bodies where they will eat mosquito larvae.

But these busy and useful creatures have a dark side. Parasitic copepods – fish lice – live on the external surfaces of fish and cause hundreds of millions of dollars of damage in farmed salmon. Controlling fish lice is an ongoing problem.

Understanding parasitic copepods has been the core of Geoff’s career. He first heard the word “copepod” when, as an undergraduate, he was working at the University’s marine biology field station at Robin Hood’s Bay on the Yorkshire coast. His mentor was Robert Wynne Owen (1924–1985), an authority on the parasites of fish. Geoff would bring Owen a parasite and he would say “goodness, I don’t know what that is, it must be a copepod”. And that was it. Geoff’s course was set.

After gaining his degree in zoology he stayed at Leeds to do a PhD on parasitic copepods, working under Owen’s tutelage at Robin Hood’s Bay. Owen knew about parasitology – just not about parasitic copepods. “I don’t know anything about them,” he told his young protégé. “It would be interesting to learn together”.

After submitting his doctorate, Geoff cast around for a lectureship in parasitology at a British university, but none were advertised that year. But, it so happened that the Natural History Museum in London (NHM) was advertising for a copepod specialist. “The only time in a century, I imagine, that they were so specific in what they were looking for,” he recalls.

The NHM has a magnetic attraction for any young scientist interested in the diversity of life on our planet. Having moved from Hampshire to London at the age of 16, the Museum was an obvious destination, only “a few pennies on the number 30 bus – a very alluring place, and I loved it. So when I got offered a job there I just jumped at it and never really regretted it.”

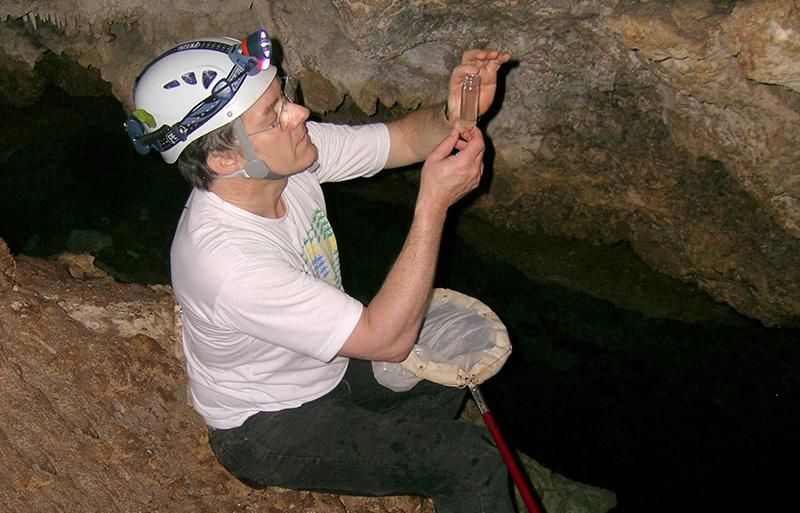

That was 1974 – he stayed until his retirement in 2017. Even then he went in three or four days a week, but then COVID-19 hit. He moved his museum microscopes to his home and caught up with the housekeeping of describing hundreds of copepods new to science.

His first NHM job had a catch, though. The job involved expertise in planktonic copepods, rather than parasitic ones. He made the leap and for his first five years became immersed in the very different world of planktonic copepods – living free and busy lives supporting the global food chain, in the sunlit surface layer of the ocean. “That was the making of me”, he says.

Museum scientists represent the public face of biology and are obliged to deal with inquiries from wherever they might come. One of the most memorable came from New York City. Copepods had been found in the drinking water supply, and Geoff became involved in the question of whether drinking tap water might be permissible for Jewish residents, as crustaceans are not kosher. (The solution was to filter the water before use).

Copepods really do get wherever there is water, and Geoff didn’t have to go far to look for specimens. They swarmed in a water tank on the Museum roof “so I could get copepods on tap”.

What drew young Geoff to Leeds in the first place? Leeds was not the obvious choice. It was initially ruled out as being too far away. “I drew a 200-mile radius and Leeds was 201 miles from where we lived”. But he was interested in marine biology, and the allure of the University’s marine lab at Robin Hood’s Bay made it worth going that extra mile.

Back in the 1960s the Zoology department was in the Baines Wing, designed by that doyen of the Victorian Gothic Revival, Alfred Waterhouse – the same architect behind the Natural History Museum. “I’ve spent my entire career in Waterhouse buildings,” says Geoff.

He rubbed shoulders with some of the legendary figures of biology. Robert McNeill Alexander joined the department in 1969. He was renowned for his expertise on how animals moved. Although laden with academic awards, his favourite was rumoured to be that conferred by The Mail on Sunday which listed him as one of “Britain's Nuttiest Professors — Ten Sages Who Really Know Their Onions”.

Geoff’s time at Leeds coincided with the reign of the formidable Manton sisters. Irene Manton, pioneer of electron microscopy of plant cells, was Professor of Botany. When Geoff moved to the NHM he found that he was in the office next door to her sister Sidnie.

The University of Leeds in the 1960s was a hive of activity. “In 1968 when I started, Jack Straw (who became Cabinet Minister in the Blair and Brown Labour governments) was the president of the Students Union and led sit-ins in the admin block. They were exciting times.”

Not that Geoff took much notice – at least, not to start with. He was too busy studying, as he thought “everyone was going to be a lot cleverer than I was”. It was only when he got a prize for academic distinction at the end of his first year that he realised that everyone else was having fun.

At one stage he shared a house with a bunch of language students and came back after a lab session to find them “sitting around describing the colour patterns on the ceiling. They’d had LSD in their beef stew at lunchtime, and they were all tripping. It took me a disgustingly long time to work out what was going on.”

Friends pulled Geoff out of his shell. He played rugby, joined the Rock Climbing Society and enjoyed the music scene. When The Who recorded their legendary live album Live at Leeds in the Refectory on 14 February 1970, Geoff was there. Perhaps you can hear him in the crowd.

A flatmate he’d known from schooldays dragged him along to university drama clubs. He saw a lot of student theatre. He was also interested in folk music. The same flatmate said he simply had to come and see “this fantastic girl singer. So I did, and eventually married her”. To cap it all, “I finished my undergraduate years with a profit of £21 from my student grant. Think how different it is nowadays.”

More information

© Henry Gee. About the writer: Henry Gee (Genetics and Zoology 1984) is an author and a Senior Editor of Nature magazine. His latest book is ‘A (Very) Short History of Life on Earth’.

Share your news with us

Do you have a story to share? We welcome updates from our alumni, no matter how long ago you were here.