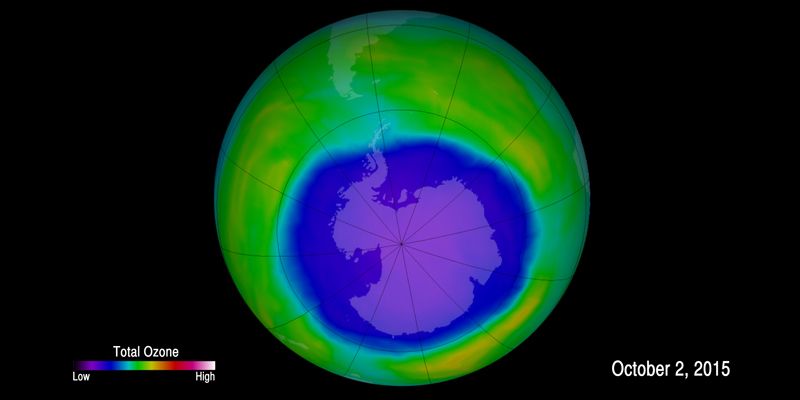

Scientists have observed clear signs that the hole in the Antarctic ozone layer is beginning to close.

The scientists from the University of Leeds were part of an international team, led by Professor Susan Solomon of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The research confirmed the first signs of healing of the ozone layer, which shields life on Earth from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays.

Recovery of the hole has varied from year to year, due in part to the effects of volcanic eruptions.

But accounting for the effects of these eruptions allowed the team to show that the ozone hole is healing, and they see no reason why the ozone hole should not close permanently by the middle of this century.

These encouraging new findings, published today in the journal Science, show that the average size of the ozone hole each September has shrunk by more than 1.7 million square miles since 2000 – about 18 times the area of the United Kingdom.

The research attributes this improvement to the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which heralded a ban the use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) – then widely used in cooling appliances and aerosol cans.

Professor Solomon said: “We can now be confident that the things we’ve done have put the planet on a path to heal.

"We decided collectively, as a world, ‘Let’s get rid of these molecules’. We got rid of them, and now we’re seeing the planet respond.”

Co-author Dr Ryan R Neely III, a Lecturer in Observational Atmospheric Science at the Leeds-based National Centre for Atmospheric Science and Leeds’ School of Earth and Environment, said: “Observations and computer models agree; healing of the Antarctic ozone has begun.

"We were also able to quantify the separate impacts of man-made pollutants, changes in temperature and winds, and volcanoes, on the size and magnitude of the Antarctic ozone hole.”

Leeds colleague and co-author Dr Anja Schmidt, an Academic Research Fellow in Volcanic Impacts, said: “The Montreal Protocol is a true success story that provided a solution to a global environmental issue.”

She added that the team’s research had shed new light on the part played by recent volcanic eruptions – such as at Calbuco in Chile in 2015 – in Antarctic ozone depletion.

“Despite the ozone layer recovering, there was a very large ozone hole in 2015,” she said.

“We were able to show that some recent, rather small volcanic eruptions slightly delayed the recovery of the ozone layer.

“That is because such eruptions are a sporadic source of tiny airborne particles that provide the necessary chemical conditions for the chlorine from CFCs introduced to the atmosphere to react efficiently with ozone in the atmosphere above Antarctica.

"Thus, volcanic injections of particles cause greater than usual ozone depletion.”

The ozone hole begins growing each year when the sun returns to the South Polar cap from August, and reaches its peak in October – which has traditionally been the main focus for research.

The researchers believed they would get a clearer picture of the effects of chlorine by looking earlier in the year in September, when cold winter temperatures still prevail and the ozone hole is opening up.

The team showed that as chlorine levels have decreased, the rate at which the hole opens up in September has slowed down.

Key facts

- Scientists from the British Antarctic Survey discovered in the mid-1980s that the October total ozone was dropping. From then on, scientists worldwide typically tracked ozone depletion using October measurements of Antarctic ozone

- Ozone is sensitive not just to chlorine, but also to temperature and sunlight. Chlorine eats away at ozone, but only if light is present and if the atmosphere is cold enough to create polar stratospheric clouds on which chlorine chemistry can occur

- Measurements have shown that ozone depletion starts each year in late August, as Antarctica emerges from its dark winter, and the hole is fully formed by early October

- The researchers focused on September because chlorine chemistry is firmly in control of the rate at which the hole forms at that time of year, so as chlorine has decreased, the rate of depletion has slowed down

- They tracked the yearly opening of the Antarctic ozone hole each September from 2000 to 2015, analysing ozone measurements taken from weather balloons and satellites, as well as satellite measurements of sulphur dioxide emitted by volcanoes, which can also enhance ozone depletion. And, they tracked meteorological changes, such as temperature and wind, which can shift the ozone hole back and forth.

- They then compared yearly September ozone measurements with computer simulations that predict ozone levels based on the amount of chlorine estimated to be present in the atmosphere from year to year. The researchers found that the ozone hole has declined compared to its peak size in 2000. They further found that this decline matched the model’s predictions, and that more than half the shrinkage was due solely to the reduction in atmospheric chlorine and bromine

- Chlorofluorocarbon chemicals (CFCs) last for up to 100 years in the atmosphere, so it will be many years before they disappear completely

- The reason there is an ozone hole in the Antarctic is that it is the coldest place on Earth – it is so cold that clouds form in the Antarctic stratosphere. Those clouds provide particles, surfaces on which the man-made chlorine from the chlorofluorocarbons reacts. This special chemistry is what makes ozone depletion worse in the Antarctic.

Further information

Photo credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Scientists from the Atmospheric Chemistry Observations and Modeling (ACOM) Laboratory at National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, also worked on the research, which was supported in part by the National Science Foundation and the US Department of Energy.

The paper, Emergence of Healing in the Antarctic Ozone Layer, is published in Science today (DOI: 10.1126/science.aae0061). For copies of the paper, interviews, images or further information, contact Gareth Dant, University of Leeds Media Relations Manager, on 0113 343 3996 or email g.j.dant@leeds.ac.uk.