The walls of the human heart are a disorganised jumble of tissue until relatively late in pregnancy despite having the shape of a fully functioning heart, according to a pioneering study.

A University of Leeds-led team developing the first comprehensive model of human heart development using observations of living foetal hearts found surprising differences from existing animal models.

Although they saw four clearly defined chambers in the foetal heart from the eighth week of pregnancy, they did not find organised muscle tissue until the 20th week, much later than expected.

Developing an accurate, computerised simulation of the foetal heart is critical to understanding normal heart development in the womb and, eventually, to opening new ways of detecting and dealing with some functional abnormalities early in pregnancy.

Studies of early heart development have previously been largely based on other mammals such as mice or pigs, adult hearts and dead human samples. The Leeds-led team is using scans of healthy foetuses in the womb, including one mother who volunteered to have detailed weekly ECG (electrocardiography) scans from 18 weeks until just before delivery.

This functional data is incorporated into a 3D computerised model built up using information about the structure, shape and size of the different components of the heart from two types of MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scans of dead foetuses’ hearts.

Early results from the project, which involves researchers from Leeds, the University of Edinburgh, the University of Nottingham, the University of Manchester and the University of Sheffield, show that the human heart may develop on a different timeline from other mammals.

While the tissue in the walls of a pig heart develops a highly organised structure at a relatively early stage of a foetus’ development, a paper from the Leeds-led team published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface Focus reports that the there is little organisation of the human heart’s cells until 20 weeks into pregnancy.

A pig’s pregnancy lasts about three months and the organised structure of the walls of the heart emerge in the first month of pregnancy. The new study only detected similar organised structures well into the second trimester of the human pregnancy. Human foetuses have a regular heartbeat from about 22 days.

Dr Eleftheria Pervolaraki, Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Leeds’ School of Biomedical Sciences, said: “For a heart to be beating effectively, we thought you needed a smoothly changing orientation of the muscle cells through the walls of the heart chambers. Such an organisation is seen in the hearts of all healthy adult mammals.

“Foetal hearts in other mammals such as pigs, which we have been using as models, show such an organisation even early in gestation, with a smooth change in cell orientation going through the heart wall. But what we actually found is that such organisation was not detectable in the human foetus before 20 weeks,” she said.

Professor Arun Holden, also from Leeds’ School of Biomedical Sciences, said: “The development of the foetal human heart is on a totally different timeline, a slower timeline, from the model that was being used before. This upsets our assumptions and raises new questions. Since the wall of the heart is structurally disorganised, we might expect to find arrhythmias, which are a bad sign in an adult. It may well be that in the early stages of development of the heart arrhythmias are not necessarily pathological and that there is no need to panic if we find them. Alternatively, we could find that the disorganisation in the tissue does not actually lead to arrhythmia.”

A detailed computer model of the activity and architecture of the developing heart will help make sense of the limited information doctors can obtain about the foetus using non-invasive monitoring of a pregnant woman.

Professor Holden said: “It is different from dealing with an adult, where you can look at the geometry of an individual’s heart using MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) or CT (Computerised Tomography) scans. You can’t squirt x-rays at a foetus and we also currently tend to avoid MRI, so we need a model into which we can put the information we do have access to.”

He added: “Effectively, at the moment, foetal ECGs are not really used. The textbooks descriptions of the development of the human heart are still founded on animal models and 19th century collections of abnormalities in museums. If you are trying to detect abnormal activity in foetal hearts, you are only talking about third trimester and postnatal care of premature babies. By looking at how the human heart actually develops in real life and creating a quantitative, descriptive model of its architecture and activity from the start of a pregnancy to birth, you are expanding electrocardiology into the foetus.”

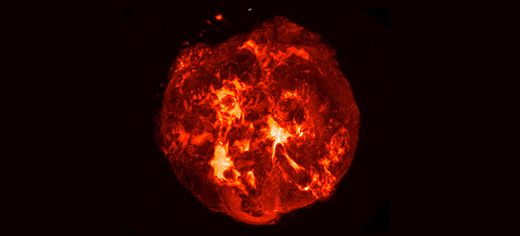

Image information: A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the heart of a 139-day-old foetus, seen from the top. The red colour highlights muscle cells.

Further information:

For interviews, please contact Chris Bunting, Press Officer, University of Leeds; phone +44 113 343 2049 or email c.j.bunting@leeds.ac.uk

The full paper, “Antenatal architecture and activity of the human heart,” is published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface Focus and has been published online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2012.0065 (DOI: 10.1098/rsfs.2012.0065).