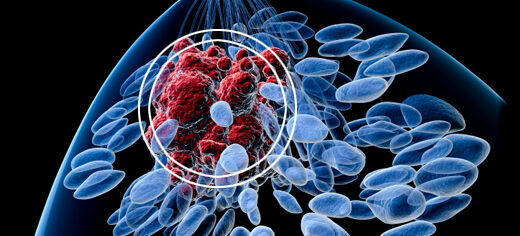

Breast cancer survivors treated with chemotherapy could be vulnerable to common illnesses because of the long-term impact on the body’s immune response, according to new research findings.

Chemotherapy is used to treat 30% of breast cancer patients and whilst previous studies have investigated its effects on immune systems during the therapy itself - and up to a short period after the last treatment - little is known about the long-term impact on immunity.

Researchers from University of Leeds and Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust measured the levels of lymphocytes, a group of white blood cells involved in the body’s immune response, together with antibodies.

They found that chemotherapy reduced levels of some immune system components for at least nine months after treatment.

These changes may leave breast cancer chemotherapy patients vulnerable to specific infections, despite having had routine vaccinations for such infections years before.

The findings, published in the open access journal Breast Cancer Research, raises the possibility that survivors could benefit from additional post-treatment monitoring.

Dr Thomas Hughes, Associate Professor in the School of Medicine at the University of Leeds, led the research with Dr Clive Carter, Honorary Senior Lecturer in the School of Medicine.

Dr Hughes said: “We were surprised that the impact of chemotherapy is so long lived. We were also surprised that smoking and choice of chemotherapy agent influenced the dynamics of the recovery of the immune system.

"We might need to take into account the future immune health of breast cancer patients when planning treatments, but more research is needed to determine whether this would improve patient outcomes.”

Further research is also required to assess if revaccination would be beneficial.

Investigating the immune system of 88 women with breast cancer, levels of lymphocytes were measured before and at intervals between two weeks and nine months after chemotherapy. There was no pre-chemotherapy data for 26 of these participants.

Levels of all the major types of lymphocytes dropped significantly after chemotherapy. This included T and B cells and natural killer cells, which together defend the body against viral and bacterial infection.

The impact of chemotherapy on most lymphocytes was found to be only short term, with recovery to pre-chemotherapy levels by nine months.

However, chemotherapy had a long term effect on B cells (cells that ultimately produce antibodies) and helper T cells (cells that are responsible for helping antibody production), both of which only partially recovered to around 65% of initial levels in the first six months and did not continue to recover after a further three months.

Levels of antibodies against tetanus and pneumococcus (the bacterium that can lead to pneumonia) also were reduced and stayed low even after nine months.

Chemotherapy uses different chemical agents. The researchers compared an anthracycline-only regime with anthracyclines followed by taxane cycles.

The anthracyclines regime was more damaging to B cells and helper T cells initially, although after this treatment, recovery was relatively effective.

On the other hand, anthracyclines followed by taxanes was associated with sustained reductions in levels of immune cells with poor recovery.

Smoking also appeared to slow down the recovery of some immune cells, with levels in smokers reaching only half pre-chemotherapy levels after nine months compared to 80% in non-smokers.

Although the observational longitudinal study can increase understanding of the links between chemotherapy, smoking and immune defence, it cannot show cause and effect because other factors may play a role.

Further information

Dr Thomas Hughes is available for interview. Contact Ben Jones in the University of Leeds press office on 0113 343 8059 or email B.P.Jones@leeds.ac.uk

The full paper "Lymphocyte depletion and repopulation after chemotherapy for primary breast cancer" is published in Breast Cancer Research.