The work of the University of Leeds professor who developed one of the most influential scientific techniques of the 20th Century has been commemorated 100 years after he received the Nobel Prize.

A bust of Sir William Henry Bragg, Cavendish Chair of Physics at Leeds from 1909 to 1915, who with his son William Lawrence Bragg won the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics for the development of X-ray crystallography, was unveiled today in the University’s Parkinson Court.

Their research revolutionised science by allowing researchers to examine the atomic structure of materials in detail for the first time.

Sir Alan Langlands, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Leeds, said: “Looking back at the century since the 1915 Nobel Prize, it is hard to exaggerate the significance of the Braggs' contribution. At least 20 subsequent Nobel prizes in physics, chemistry and medicine, including Watson and Crick’s momentous work on the structure of DNA, relied directly on X-ray diffraction.

“The Braggs’ legacy is felt in all of our lives. The medical ultrasound device that produces pictures of your baby, the fuel injectors in cars, the SONAR used in submarines, to take just a few examples, all rely on materials developed using X-ray crystallography. Our knowledge of biology, chemistry, medicine, materials science, electronic materials, pharmacology and many other areas would be immeasurably poorer without them.”

The new bust, a bronze cast by the Australian artist Robert Hannaford, has initially been installed in the University’s Parkinson Court, but is expected to be moved to the Bragg Centre, a new interdisciplinary research centre in engineering and the physical sciences recently approved by the University’s Council. An identical bust has been installed at the University of Adelaide, where William Henry Bragg gained his first professorship.

The crucial steps in the development of X-ray crystallography were taken in the physics laboratories at the University of Leeds in 1912-13.

William Lawrence Bragg, a junior researcher at Cambridge, first suggested the concept behind the technique in 1912. His father, William Henry Bragg, then developed the first X-ray spectrometer soon after at Leeds. By directing X-rays through matter and recording the resulting diffraction pattern on photographic plates, the pair found they could determine the atomic structure of crystallised materials.

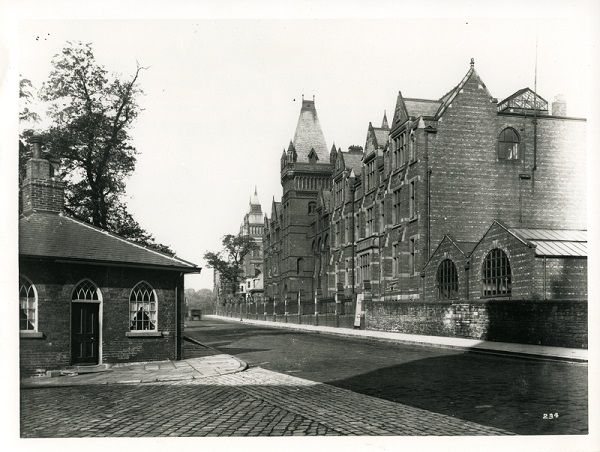

They spent the 1912 Christmas holidays and much of the next year at the University’s physics labs (near what is now the Parkinson Building) developing the technique and applying it to the structure analysis of crystals. William Lawrence Bragg later recalled: “It was a wonderful time, like discovering a new goldfield where nuggets could be picked up on the ground, with thrilling new results almost every week.”

By the time their Nobel Prize was announced in November 1915, William Lawrence Bragg was serving in the Royal Horse Artillery on the Western Front at Ypres. Sir William Henry Bragg had learned only weeks before the announcement that his youngest son, Robert, had been killed at Gallipoli. He telegraphed his acceptance (“My son and I are greatly honoured indeed”), but there was no Nobel Prize ceremony that year because of the war. William Henry Bragg never travelled to Sweden to receive his prize.

Today, the legacy of the Braggs’ work flourishes at the University of Leeds with world leading research groups using X-ray diffraction and other structure analysis techniques across our faculties of Biological Sciences, Maths and Physical Sciences, Medicine and Engineering.

Professor Sheena Radford FRS, Astbury Professor of Biophysics and the Director of the Astbury Centre for Structural Molecular Biology, unveiled the bust of Bragg with Professor Alan Watson, FRS Emeritus Professor in the Faculty of Maths and Physical Sciences.

Professor Radford said: “More than 100,000 structures of proteins and their complexes have now been solved using X-ray crystallography. These structures, determined using Bragg’s laws of the crystalline diffraction of X-rays, have revealed how some of the most complex macromolecular machines in our cells work.

“But this work is far from over. Structural biology has never been more exciting than it is at this moment, with other techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance and electron microscopy adding to our armoury of methods to determine macromolecular structures in atomic detail. The last 100 years have seen a revolution in structural biology; the next 100 years promise even more.”

Professor Sven Schroeder, the Royal Academy of Engineering Bragg Centenary Chair in the University's Faculty of Engineering, said: “The ability to look at matter on the atomic scale still underpins much of our work at Leeds today. It seems appropriate that William Henry Bragg’s bust will eventually be installed in the new Bragg Centre, where in various ways his legacy will live on in areas as diverse as the fabrication of advanced semiconductors, optoelectronics, nano-technology, drug delivery and the engineering of formulated products.”

Professor Schroeder, whose role involves close collaboration with the Diamond Light Source, the UK’s synchrotron radiation facility, said: “We are not standing still. For instance, we are using intense X-rays at Diamond in novel methods for understanding the structure of molecules in liquid solutions, which impact on virtually all disciplines of engineering as well as the physical and life sciences.”

Further information

Contact: University of Leeds press office, +44 113 343 4031 or email pressoffice@leeds.ac.uk

Photograph: The old physics sheds are shown at the bottom right of the image depicting the University of Leeds Baines Wing.