Fundamental changes in our economies are required to secure decent living standards for all in the struggle against climate breakdown, according to new research.

Governments need to dramatically improve public services, reduce income disparities, scale back resource extraction and abandon economic growth in affluent countries, if people around the world are to thrive at the same time that a 50% cut in global average energy use is made.

Without such fundamental changes, the study warns, we face an existential dilemma: in our current economic system, the energy savings required to avert catastrophic climate changes might undermine living standards, while the improvements in living standards required to end material poverty would need large increases in energy use, further exacerbating climate breakdown.

The study, led by the University and published in Global Environmental Change, examined what policies could enable countries to use less energy whilst providing the whole population with “decent living standards” – conditions that satisfy fundamental human needs for food, water, sanitation, health, education, and livelihoods.

Lead author Jefim Vogel, PhD researcher at Leeds’ Sustainability Research Institute, explained: “Decent living standards are crucial for human wellbeing, and reducing global energy use is crucial for averting catastrophic climate changes. Truly sustainable development would mean providing decent living standards for everyone at much lower, sustainable levels of energy and resource use.

“But in the current economic system, no country in the world accomplishes that – not even close. It appears that our economic system is fundamentally misaligned with the aspirations of sustainable development: it is unfit for the challenges of the 21st century.”

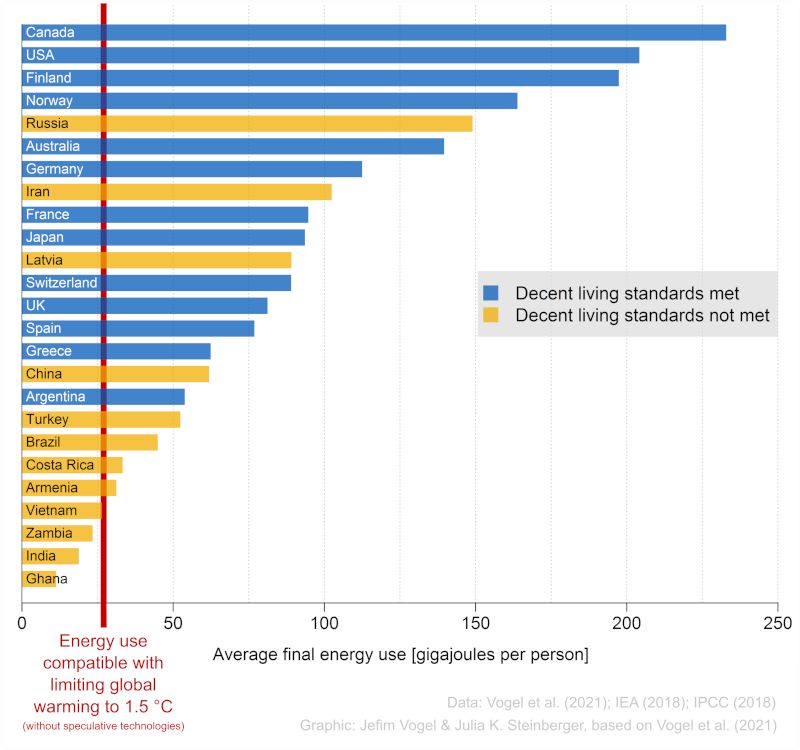

Energy use per person

Co-author Professor Julia Steinberger, from the Universities of Leeds and Lausanne in Switzerland, added: “The problem is that in our current economic system, all countries that achieve decent living standards use much more energy than what can be sustained if we are to avert dangerous climate breakdown.”

By 2050, global energy use needs to be as low as 27 gigajoules (GJ) of final energy per person to reach the aspirations of the Paris Agreement of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C without relying on speculative future technologies, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

That means current global average energy use (55 GJ per person) needs to be cut in half, while affluent countries like the UK (81 GJ per person) or Spain (77 GJ per person) need to reduce their average energy use by as much as 65%, France (95 GJ per person) by more than 70%, and the most energy-hungry countries like the USA (204 GJ per person) or Canada (232 GJ per person) need to cut by as much as 90%.

A major concern, however, is that such profound reductions in energy use might undermine living standards, as currently only countries with high energy use accomplish decent living standards.

Even the energy-lightest of the countries that achieve decent living standards – spearheaded by Argentina (53 GJ per person), Cyprus (55 GJ per person), and Greece (63 GJ per person) – use at least double the ‘sustainable’ level of 27 GJ per person, and many countries use even much more.

On the other hand, in all countries with energy use levels below 27 GJ per person, large parts of the population currently suffer from precarious living standards – for example, in India (19 GJ per person) and Zambia (23 GJ per person), where at least half the population is deprived of fundamental needs.

Improving living standards

It appears that in the current economic system, reducing energy use in affluent countries could undermine living standards, while improving living standards in less affluent countries would require large increases in energy use and thus further exacerbate climate breakdown.

But this is not inevitable, the research team show: fundamental changes in economic and social priorities could resolve this dilemma of sustainable development.

Co-author Dr Daniel O’Neill, from Leeds’ School of Earth and Environment, explained: “Our findings suggest that improving public services could enable countries to provide decent living standards at lower levels of energy use. Governments should offer free and high-quality public services in areas such as health, education, and public transport.

“We also found that a fairer income distribution is crucial for achieving decent living standards at low energy use. To reduce existing income disparities, governments could raise minimum wages, provide a Universal Basic Income, and introduce a maximum income level. We also need much higher taxes on high incomes, and lower taxes on low incomes.”

Modern fuels

Another essential factor, the research team found, is affordable and reliable access to electricity and modern fuels. While this is already near-universal in affluent countries, it is still lacking for billions of people in lower-income countries, highlighting important infrastructure needs.

Perhaps the most crucial and perhaps the most surprising finding is that economic growth beyond moderate levels of affluence is detrimental for aspirations of sustainable development.

Professor Steinberger explained: “In contrast with wide-spread assumptions, the evidence suggests that decent living standards require neither perpetual economic growth nor high levels of affluence.

“In fact, economic growth in affluent or even moderately affluent countries is detrimental for living standards. And it is also fundamentally unsustainable: economic growth is tied to increases in energy use, and thus makes the energy savings that are required for tackling climate breakdown virtually impossible.

“Another detrimental factor is the extraction of natural resources such as coal, oil, gas or minerals – these industries need to be scaled back rapidly.”

Jefim Vogel concluded: “In short, we need to abandon economic growth in affluent countries, scale back resource extraction, and prioritise public services, basic infrastructures and fair income distributions everywhere.

“With these policies in place, rich countries could slash their energy use and emissions whilst maintaining or even improving living standards; and less affluent countries could achieve decent living standards and end material poverty without needing vast amounts of energy. That’s good news for climate justice, good news for human well-being, good news for poverty eradication, and good news for energy security.

“But we need to be clear that achieving this ultimately requires a broader, more fundamental transformation of our growth-dependent economic system. In my view, the most promising and integral vision for the required transformation is the idea of degrowth – it is an idea whose time has come.”

Further information

The paper, “Socio-economic conditions for satisfying human needs at low energy use: an international analysis of social provisioning”, is published in Global Environmental Change on 30 June 2021.

DOI: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102287.

The research team included:

Jefim Vogel (Sustainability Research Institute, School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, UK).

Julia K. Steinberger (Institute of Geography and Sustainability, Faculty of Geosciences and Environment, University of Lausanne, Switzerland; Sustainability Research Institute, School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, UK).

Daniel W. O’Neill (Sustainability Research Institute, School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, UK).

William F. Lamb (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, Berlin, Germany; Sustainability Research Institute, School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, UK).

Jaya Krishnakumar (Institute of Economics and Econometrics, Geneva School of Economics and Management, University of Geneva, Switzerland).

The study was initiated by the “Living Well Within Limits” project, led by Professor Julia Steinberger.

The research of Jefim Vogel and Julia Steinberger was funded by the Leverhulme Trust.

For more information, contact Ian Rosser in the Press Office at the University of Leeds by email on i.rosser@leeds.ac.uk.