By Lisa Harris (University of Exeter), Sarah Dyer (University of Manchester), and Arunangsu Chatterjee (University of Leeds)

‘Reply all’ is a historical example of technology-led change.

Large sums of money were spent on the introduction of institutional email communication systems and on training staff, but how people use these digital tools is informed by their needs, expectations, and bandwidth for change.

The consequences of the ubiquitous ‘reply all’ email are often annoying, sometimes amusing, rarely efficient, and occasionally institutionally risky. Our hope is that lessons can be learned and such experiences avoided with the current opportunities and challenges of digital transformation.

A group of us will be coming together for the Times Higher Education Digital Universities conference at the University of Leeds (April 17–20) to consider an alternative to ‘technology-first’ digital change, the challenges posed by change in large complex organisations, and how digital transformation can be facilitated in ways that lead to meaningful, sustainable change.

Ahead of our session during the conference, we want to provide some context and set out the objectives for our panel discussion and its follow-on workshop.

Digital transformation, according to Accenture, ‘is the process by which companies embed technologies across their businesses to drive fundamental change’. Simple technology-focused statements such as this do little to support the practical realities of managing digital change in large, complex organisations such as universities.

We must understand digital transformation as being a culture change:

...a series of deep and coordinated culture, workforce and technology shifts that enable new educational and operating models and transform an institution’s operations, strategic directions, and value proposition.

Why is digital transformation necessary in higher education?

The pandemic highlighted the importance of flexibility and inclusivity in how we engage with our students and collaborate with our colleagues in a variety of workspaces. It showed how change can happen quickly if necessary, and that developments in digital technologies have raised the expectations of stakeholders to a whole new level.

What for years we’ve naively been calling ‘the future of work’ is now actually ‘the present of work’. As educators, we have a responsibility to prepare our students for success in their future careers. This imperative extends far beyond the transfer of subject-specific knowledge.

Innovators have long been calling for culture change which enables innovation through collaboration and inclusivity - as we discussed in our WonkHE blog, How to shape digital culture in higher education.

While there are a few models which we will highlight, evidence suggests that many institutions are making very slow progress or even regressing to their pre-pandemic priorities.

Teaching and exams are being pulled back onto campus, with new technology projects still bolted onto existing systems and processes. There is often no collective ‘ownership’ of the digital agenda or even an understanding of what it means for everyone in the institution. The prevailing narrative is ‘back to normal’. This position is summed up in the findings of a recent survey by Jisc.

Why is change so difficult?

Bringing about digital transformation in these large and organisationally complex universities requires us to stop conceptualising digital projects as additive; that is simply adding digital tools to the systems as they are.

Even the most straightforward of projects - say automating existing processes, is a job akin to performing open heart surgery on a patient who is running a marathon. To successfully perform this ‘surgery’, the diverse needs, interests, and behaviours of the people involved need to be paramount.

Administrative processes evolve as they are undertaken. For example, one group might find a workaround for something that didn’t quite work for them, whilst another group had to use the process for something it wasn’t designed for. The process is therefore changed to fit other processes and systems that it interfaces with.

There is no easy technical ‘fix’ that we can add to existing systems. The size, shape, and requirements of universities have changed. We need to understand the diversity of needs a technology must serve, and the complexity of the associated organisational requirements.

We have the opportunity to undertake transformational digital adoptions. We need to be reviewing people’s needs and how processes work, and be looking for transformative change in which we re-think the associated working practices at all levels of the organisation in ways that simply weren’t possible before. We believe this is an existential concern for universities.

Some frameworks have emerged in other organisations which might be useful in helping to drive change. For example, Alan Brown’s review of publications over the past 10 years based on digital transformation strategies in government, concludes that little progress has been made so far.

He notes that the latest book by Gerry Fishenden, “Fracture: The collision between technology and democracy – and how we fix it”, puts emphasis on leadership and policy rather than technology, with the aim of “learning smarter, acting faster, and adapting better”.

Sarah Pena, writing for Digital Leaders, talks about the emerging “5th Industrial Revolution” where people and technology collaborate to add value in a very different language from the fourth.

In higher education, Jisc has published a comprehensive checklist for digital transformation which highlights effective leadership as a critical success factor.

While a range of frameworks exists to aid digital transformation, there is a significant gap in execution approaches or case studies, particularly in the context of higher education institutions.

Examples from other public sector initiatives like the NHS reveal a similar pattern where a lack of meaningful end user engagement impedes large-scale digital transformation efforts.

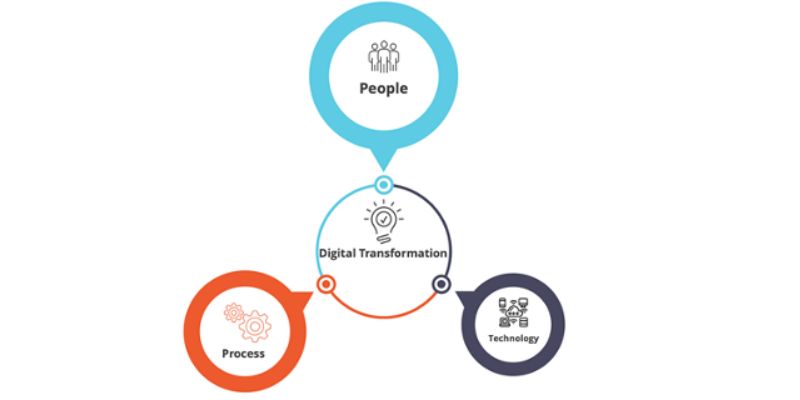

We believe the fundamental principle of digital transformation is to put people first, followed by processes and then finally tools. It needs to begin by understanding these needs. Making this commitment, a whole host of things become much clearer, for example how the digital transformation process should be executed, with what aims and accountabilities, what skills are required and how teams should be made up.

A few Universities have embarked on this journey and started to express how their digital transformation ambitions will be anchored around a people-first approach augmented with an evolving constructivist view of designing experiential opportunities and building on from digitalisation efforts.

THE Digital Universities UK panel session

We are looking forward to sharing experiences of digital change, good and bad, in our panel session at #THEdigitalUK.

To ensure that the energy and ideas exchanged in the room are captured, we will be running a workshop immediately afterwards. In this session, participants will be invited to collaboratively develop a manifesto for change that can be shared and refined at future THE events around the world.

Top image credit: Glenn Carstens-Peters via unsplash.com.