Interview: The art of ageing

Artist and researcher Garry Barker has always used his art as a way to engage with the surrounding world. As he grew older, his work began to focus on issues commonly faced by older adults, and this shift led him to amplify the feelings around ageing through drawings and small sculptures.

In September 2024, Garry was awarded a prize for the best conference poster at the Reimagine Ageing Showcase at the University of Leeds. We asked him some questions about his work and career.

What made you get into this type of work and what drives you?

The simple fact that I was getting older and that my work as an artist had always been a response to the world around me meant that my thoughts and reflections on life had to include the fact that I was having to face the typical issues older people encounter.

This included invisibility, people began asking me if I had retired, growing awareness that my body wasn’t as mobile and strong as it used to be, a tendency to reminisce, my memory was beginning to get worse, my hearing was going and the world seemed to have changed a hell of a lot since I began my career as an artist.

I have always worked as an artist and never wanted to do anything else and am driven by the hope that at some point I will produce that piece of work that will mean something really important to someone.

Tell us about your work.

As an artist, I reflect upon the world as it impacts on me. I work to find a synthesis between an awareness of my body, the environment I find myself in and the various conceptual frameworks that I find useful to my sense making.

For instance, I am very interested in animist ways of thinking. This allows me as an artist to develop a sort of ventriloquist’s voice, by using my artwork to imagine what is it like to be something that is not human and then letting it ‘speak’. Older societies have used aspects of this type of thinking to develop sympathetic magic, whilst I use it to develop analogies and similes to explain complex ideas.

Basically, I am using materialisations of the world such as shaping a lump of clay or making marks on a surface to think with and to communicate with other people.

What has surprised you the most in your career?

How long it has lasted. I began teaching at the Jacob Kramer College, focusing on drawing as a problem-solving tool in January 1975, and I’m still at the same institution (although it is now called the Leeds Arts University). Now as a researcher, I’m still looking at how drawing can be used to visualise the way we understand the world.

I see too many older people who feel that their contribution to society is over and that they are now a burden on others.

If you had a wand – what would be the one and first thing you would improve for older people?

Self-worth. I see too many older people who feel that their contribution to society is over and that they are now a burden on others. I feel we need to learn from other cultures whereby older people are revered for their life knowledge and wisdom.

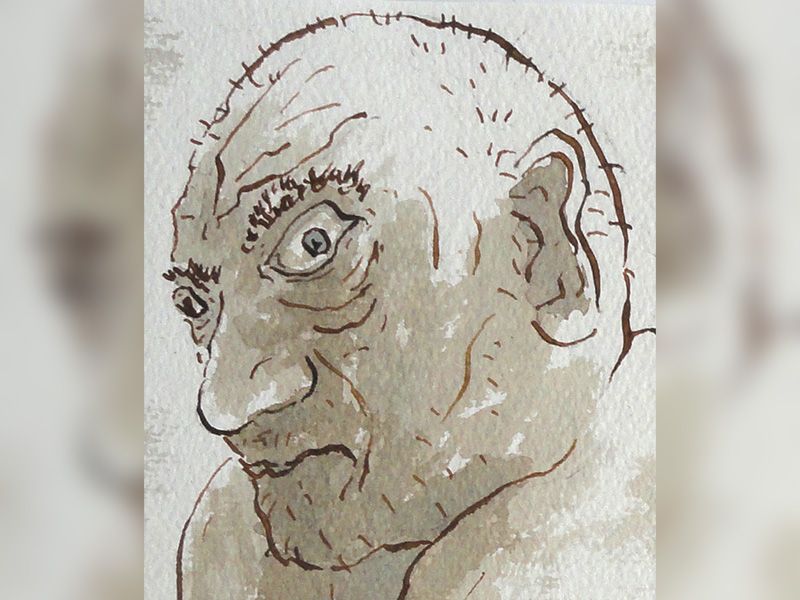

Self-portrait by Garry Barker.

How do you (re)imagine a world where the ageing population is thriving?

A world where older people are integrated into everyone’s day-to-day lives and not pulled out of society as they are perceived to be unable to look after themselves. Perhaps systems whereby families and friends/neighbours etc. are expected to take responsibility for others and trained in the necessary skills needed to support people as they get older.

How would you describe your proudest achievement workwise?

To have taught and helped several generations of students to think using drawing as a problem-solving tool and to hopefully have fostered their creativity and belief in themselves.

I feel we need to learn from other cultures whereby older people are revered for their life knowledge and wisdom.

What is your favourite inspirational quote?

The Japanese artist Hokusai had this to say:

“From around the age of six, I had the habit of sketching from life. I became an artist and from fifty on began producing works that won some reputation, but nothing I did before the age of seventy was worthy of attention. At seventy-three, I began to grasp the structures of birds and beasts, insects and fish, and of the way plants grow.

If I go on trying, I will surely understand them still better by the time I am eighty-six, so that by ninety I will have penetrated to their essential nature. At one hundred, I may well have a positively divine understanding of them, while at one hundred and thirty, forty, or more I will have reached the stage where every dot and every stroke I paint will be alive. May Heaven, that grants long life, give me the chance to prove that this is no lie.”

Hokusai died at the age of 90.