Held by Cultural Collections at the University of Leeds, the earliest-known English book about cheese is revealing its fascinating and sometimes nauseating contents to the public for the first time.

A new transcription, made by Tudor re-enactors at Kentwell Hall, is now available to read online alongside the digital version of the original handwritten manuscript.

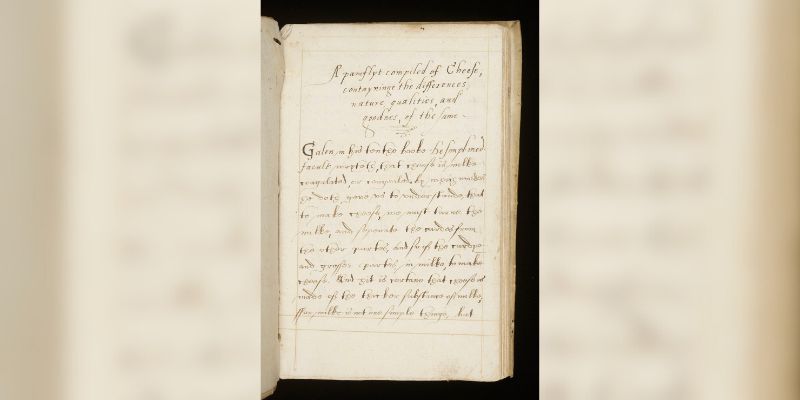

‘A pamflyt compiled of Cheese, contayninge the differences, nature, qualities, and goodnes, of the same’ was unpublished and unknown until it surfaced at auction in 2023 and was acquired by the University with the support of a grant from Friends of the Nation’s Libraries. The 112-page vellum-bound manuscript is thought to date from the 1580s.

“Over the last 50 years we’ve seen a great revival of English cheeses of every variety”, says food historian Peter Brears. “The ‘Pamflyt’ really shows us that we have a cheese heritage in this country.

“I’ve never seen anything like it: it’s probably the first comprehensive academic study of a single foodstuff to be written in the English language. Although cheese has formed part of our diets since prehistoric times, there was still little evidence of its character and places of production by the Tudor era. The Pamflyt shows that cheeses of different kinds were being considered, and also studied from a dietary point of view.”

Image: The introductory page of the pamflyt compiled of cheese. Credit: University of Leeds Cultural Collections

Readings from the new transcription can be heard for the first time on the latest episode of BBC Radio 4’s Food Programme. Presenter Sheila Dillon also visits a modern-day cheesemaker in Yorkshire to bring one of the Tudor recipes back to life.

“What first struck me was that it was written in an incredibly neat hand”, says Dr Alex Bamji, Associate Professor of Early Modern History at the University of Leeds’ School of History. “It’s a substantial piece of work: ‘Treatise’ might be a better word to describe it. As with other treatises from this period, the writer has woven together ancient knowledge with their own learning and experience. It’s such a great fit with what we know about how people understood the role of diet in health in the period. Food was useful both to prevent and to respond to illness, and ordinary people had quite a complex understanding of that.

“One passage I particularly liked was: ‘he that will judge whether cheese be a convenyent foode for him, must consider the nature of the body, and the temperamente of the cheese and both considered he shalbe hable to judge whether he is like to take harme be cheese or not.’ The term ‘dairy intolerant’ might not have been used then, but there’s certainly an understanding here that cheese works better in some people's bodies than others – although the author explains this through the system of the ‘humors’, and the idea that your body will be either hotter or colder and dryer or more moist.

Food was useful both to prevent and to respond to illness, and ordinary people had quite a complex understanding of that.

“There's a lot of discussion about when you should eat cheese”, Dr Bamji continues. “Generally the view was that it was best towards the end of a meal, which a lot of us still subscribe to today. ‘Cheese doth presse downe the meate to the botome of the stomake’, it says, where the digestion is best.”

Other claims include the warning that dog’s milk ‘doth cause a woman to be delivered of her childe before tyme’. The author also reassures us that he has never heard of women’s milk used for cheesemaking ‘in any place’, although camel’s, ass’s and mare’s milk are used in certain places.

The new transcription was made by Ruth Bramley, who is part of a team of re-enactors at Kentwell Hall, a 16th century manor house in Suffolk that hosts regular immersive historical events. After hearing of the University of Leeds’ acquisition of the Pamflyt, she began transcribing the manuscript from the digitised version that can be seen online. “My re-enactment expertise is textiles – I’m a spinner and weaver”, says Ruth. “But I have quite a lot of experience when it comes to transcribing handwriting from the past through my family and local history research, which often involves deciphering wills and other documents.”

Image: Easter cheeses and butter at Kentwell Hall. Credit: Tracy Doyle

Her colleague Tamsin Bacchus, who works in the Tudor Dairy at Kentwell, comments: “What warmed my heart towards the author of the Pamflyt is that when he finds conflicting ideas among his learned sources, he turns to his contemporaries who actually know the work: he ‘diligently inquyred of countrey folke, who have experience in theis matters’, and they settled the argument for him.

“The debate about whether one can eat cheese on certain religious fasting days because of the animal element in the rennet feels surprisingly modern. An alternative suggested was to use fish guts to curdle the milk! It’s also reassuring to find written down what we know from our actual practice in the Kentwell Dairy: that to make a really hard cheese to keep indefinitely (‘Suffolk Thump’) you skim off all the cream. He’s a bit scathing about it, though, calling it ‘the worste kind of cheese, accordinge to our Englishe proverbe, hit is badde cheese when the butter is gone to the market’".

The concluding passage has Ancient Greek physician Galen smearing a concoction of rancid cheese and bacon fat on the ‘knotted joyntes’ of ‘a man greatly troubled with the gowte’ until ‘the skynne breake of hit selfe withowt any incisyon, and much of the cause of those harde knobs did runne owt’. In Elizabethan times as now, thinks Dr Bamji, this historic anecdote was likely to have been appreciated for its comic and repulsive oddity rather than its medical efficacy.

The identity of the book’s author remains unclear, but three owners’ names show that it was circulated in the group around the Dudleys, a family of Tudor courtiers. In a note on the flyleaf, Clement Fisher, MP for Tamworth, asks for the book to be returned to him when it has been ‘perused’; Walter Bayley, whose name appears at the end of the text, was physician to Elizabeth I; and Edward Willoughby came from another family of parliamentarians.

This pamphlet raises the question, again, of why small-scale cheese making matters.

“There are a number of names in the running”, says Peter Brears. “I look forward to somebody undertaking a PhD on it, because there are clues to its author that demand study in depth: handwriting style; evidence of regional dialects; which modern locations are actually being referred to… There’s so much more to be learnt from this manuscript”.

Presenter of The Food Programme and food journalist Sheila Dillon comments: "This pamphlet raises the question, again, of why small-scale cheese making matters. Today most of the cheese we eat comes from factory dairies, made using milk from a wide area with no link to any particular place. What the Tudors knew in the 16th century, and what science is now starting to confirm, is that cheese from different places, made from the milk of different breeds of cows, sheep and goats, creates unique flavours, smells and textures, while cheese as a complex fermented food has a unique ability to improve our health.”

The manuscript is now available to view in its original form and to read in Ruth Bramley’s transcription on the University of Leeds Cultural Collections website, and you can hear the feature on the Pamflyt on BBC Radio 4’s Food Programme via BBC Sounds.

Further information

- Main image caption: Dr Alex Bamji and Peter Brears with the pamflyt compiled of cheese. Credit: Cultural collections at the University of Leeds

- For more information contact Rowland Thomas, Media and Production Officer at the University of Leeds via email on R.Thomas6@leeds.ac.uk.